The theory has become reality in the worst possible way. A few days ago, we were talking about the CRASH Clock and how the margin for maneuver in low Earth orbit (LEO) has been reduced to less than three days. Now, the Starlink 35956 incident has just given us a reality check—or at least, a dose of space junk. It wasn’t a collision, but the result is the same: more debris on an already congested highway.

The wonky Starlink

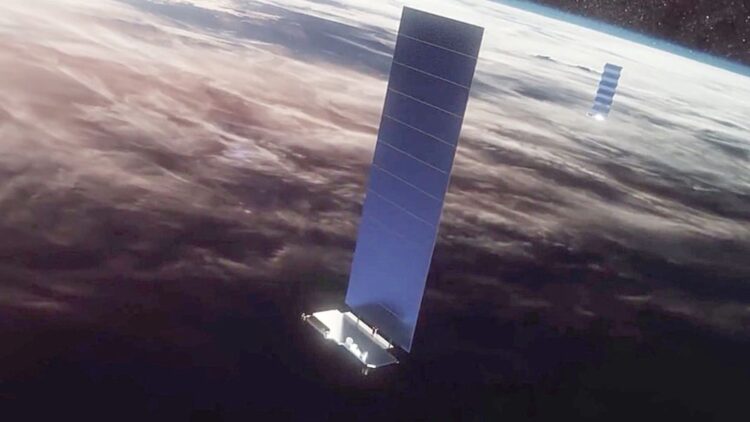

On November 23 2025, Starlink launched the Starlink Group 11-30, where the Falcon 9 rocket carried 28 satellites into orbit. This was a routine batch: the company sends up new satellites almost every week. As of December 2025, there are almost 9,400 functioning satellites doing pliés around our Planet. However, it’s stadistically impossible to have a perfect score: there have been a total of 10,839 launched satellites… and the 35956 has simply joined those who went defective.

On December 17, the 35956 satellite suffered what SpaceX euphemistically defines as an “anomaly.” LeoLabs’ tracking data is more honest: the vehicle experienced a sudden release of energy—the propellant tank ruptured, most likely. That ejected dozens of fragments 259.7 miles above Earth’s surface, yet the whole satellite remained mostly undamaged. Instead of an operational communications node, we now have a cloud of debris traveling at hypersonic speeds.

This incident is not just a technical failure (which it is); it is a crack in the security system that underpins the modern space economy. And modern humans—with our obsession with having perfect Internet connections from anywhere in the world—depend on absolute technological perfection. Starlink 35956 has proven that such perfection does not exist.

In fact, not even Starlink can connect to that satellite, which has become independent, so to speak. After the event, all communication with the satellite was lost. It is now a metal “zombie,” tumbling forever around our planet, like the orbital space trash that tormented Sandra Bullock in Gravity every few minutes.

The ISS barrier

Although SpaceX assures us that the trajectory is below the International Space Station, the risk lies in the uncertainty. Every new object on the radar is another variable in an equation that is already on the verge of collapse.

The paradox of “self-cleaning” space debris. The good news, if there is any, is that the low altitude of the incident works in our favor. The satellite and its debris will succumb to atmospheric friction and disintegrate… in a few weeks. However, the scare leaves a question hanging in the air: what would have happened if this had occurred 200 kilometers higher, where debris takes decades, not weeks, to fall?

This internal failure by SpaceX shows that it does not take a clash between powers to dirty the playground; a simple manufacturing error in a megaconstellation can be the catalyst for the “cascade” that the CRASH Clock attempts to predict.

International coordination is no longer an academic desire, it is an emergency. While SpaceX deploys software patches to prevent other satellites from following the same path, the clock keeps ticking. And it is ticking faster and faster. For now, we will have to continue waiting for economic—or prestige—incentives to go up there and start artificially collecting all the space debris we have accumulated over almost eighty years.

Since the Soviets launched Sputnik 1 into orbit in October 1957, there has been no stopping. We treat our atmosphere like an attic: we believe that the space up there is unlimited, so we send all our junk there. Someone else will take care of clearing out the junk when we’re gone, a future Marie Kondo of some sort… or maybe the house will burn down first!