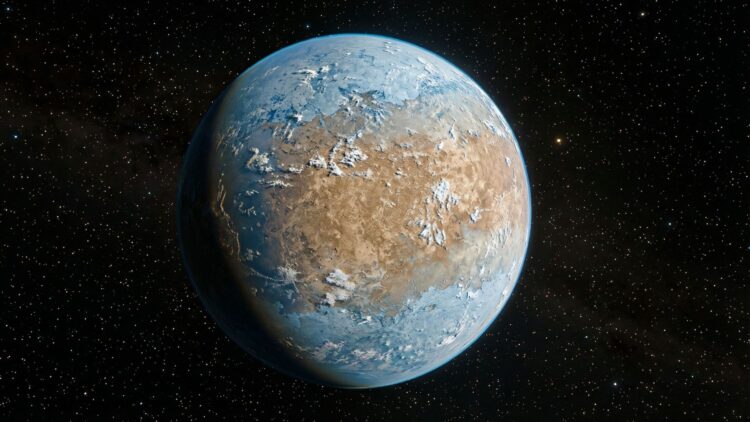

An unconfirmed world that looks a lot like our own, named HD 137010 b, possesses one major distinction: it may be even more frigid than the ice-bound world of Mars. Researchers are still digging through information from NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, which finished its mission in 2018, and they are still finding unexpected things.

A recent study shares the newest find: a potential solid world a bit bigger than Earth, circling a star like our Sun roughly 146 light-years from here.

The time it takes for this world to complete an orbit—currently called a “potential find” until more proof is found—is probably close to an Earth year. This world, HD 137010 b, might also sit right on the far boundary of the “habitable zone” of its star, which is the specific range where liquid water could exist on the ground if the air is just right.

Worlds that circle stars other than our own are called “exoplanets.” This specific one could be the very first planet like Earth that we see passing in front of a nearby, glowing Sun-like star, making it easy for us to study in more detail later on.

Freezing temperatures, Stellar Differences

Here is the unfortunate reality. The total warmth and radiation this world gets from its sun is less than one-third of what Earth gets from our Sun. Even though the star HD 137010 is a type similar to our own, it is both less warm and not as bright.

This suggests the planet’s ground temperature might not go above minus 90 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 68 degrees Celsius). For a point of reference, the typical surface temperature on Mars is roughly minus 85 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 65 degrees Celsius).

Potential ≠ Confirmation of Habitability

The world HD 137010 b also requires more study to move from being a “potential find” to a “proven discovery.” Space researchers use several different ways to find planets, and this particular find comes from just one “transit”—a single time the world passed across the front of its star like a tiny eclipse—found in the second part of the Kepler mission, called K2.

Even with only one transit, the people who wrote the study could guess how long the planet takes to orbit. They timed how long it took for the planet’s dark shape to cross the star—which lasted 10 hours, while Earth takes around 13—and then checked that against math models of the star system. All the same, even though the data from that one event is much more accurate than most transits seen by space telescopes, people who study the stars need to see these crossings happen on a fixed schedule to prove they are caused by a genuine world.

Catching more of these transits will be a challenge. Because the planet is about as far from its star as Earth is from the Sun, these crossings happen much less frequently than they do for planets hugging their stars closely (this is a major reason why worlds with Earth-like orbits are so tough to find).

If things go well, we might get proof from more sightings by the follow-up to Kepler, NASA’s TESS, which is still the main tool for finding planets, or from the European Space Agency’s CHEOPS. If that doesn’t work, getting more info on HD 137010 b might stay on hold until the next round of space telescopes is ready.

A Hidden Potential for (Human) Life on Another Planet

Even if the climate is likely freezing, the researchers behind this study suggest HD 137010 b could still be a mild or even an ocean-covered world. This would simply require an atmosphere containing more carbon dioxide than what we have on Earth.

By testing different atmospheric models, the researchers estimate there is a 40% possibility the planet sits in the “conservative” habitable area around its star, and a 51% possibility it is within the more “optimistic” habitable area. Conversely, the study’s writers mention there is roughly an even chance the planet is actually located completely outside the habitable zone.