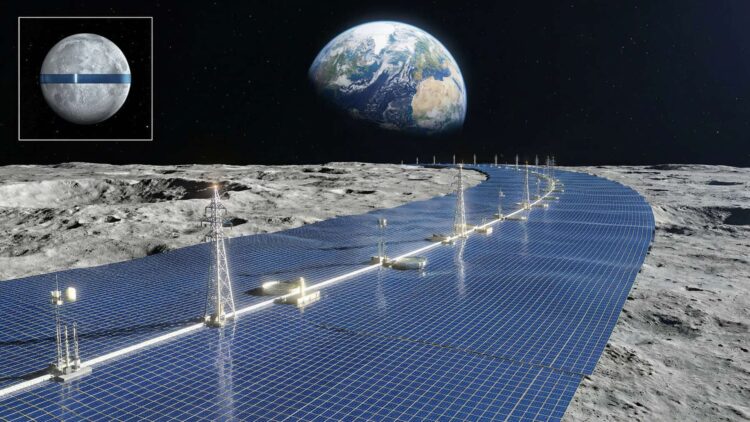

Japanese engineering giant Shimizu believes—like many others—that they have a fix for climate change: just wrap the Moon’s 6,800-mile equator in a solar panel belt that’s roughly 250 miles wide. Sounds easy peasy, right (/s)? This ring would send clean power back to Earth via microwaves, which receiving stations on the ground would then turn into usable electricity.

Pulling this off would require digging up raw materials right there on the lunar surface and building factories to manufacture the solar panels on-site. Shimizu—a company famous for wild “dream concepts” like massive pyramid cities and space hotels—explains that robots would handle the heavy lifting, such as flattening the lunar soil and digging through the hard bedrock.

The firm is aiming to kick off construction on the Luna Ring by the year 2035. According to the plan, the necessary gear would be shipped from Earth, put together in orbit, and then dropped down to the Moon’s surface to get everything set up. While this might sound like an expensive plot from a science fiction movie, the concept isn’t entirely absurd.

LUNA Ring: How it all started

Back in 2009, California officials actually gave the green light for Pacific Gas & Electric to sign a deal with a startup called Solaren; the plan was to buy 200 megawatts of power from a solar plant stationed in orbit.

This space-based solar farm was designed to use a massive inflatable mirror made of Mylar—about a kilometer across—to focus sunlight onto a smaller mirror, which would then direct those concentrated rays onto high-powered solar panels. Those panels would produce electricity, transform it into radio waves, and beam it down to a large receiving station near Fresno to be turned back into usable power.

One major advantage here is that solar panels in orbit can produce energy 24/7, unlike the ones we have on the ground. Because earthbound solar only works part of the time, it currently struggles to meet the steady, baseline demand for electricity without relying on fossil fuel plants as a backup.

That said, the price tag for launching those panels into space would be significantly higher than simply building a solar farm down here on Earth.

How the project is going

Solaren has been pretty quiet lately, but Michael Peevey, the head of the California Public Utilities Commission, mentioned in a speech last year that the project is still in the works. Peevey noted that while the idea feels like science fiction, he is hopeful that recent improvements in lighter and thinner solar tech will make it a reality. He believes the technology is worth betting on because space-based solar provides a steady stream of power, which could help replace the coal plants that usually handle that job.

However, even if the power generated by a lunar plant eventually pays off the massive cost of building it—not to mention the rocket fuel burned just to launch the gear—Wired points out that Shimizu’s biggest obstacle might be securing rights to all that land on the Moon.

Space law is famously tricky to enforce, so legal battles could easily shut down the plans long before construction ever begins.

In search of a new energy source

Up until March 2011, when a devastating earthquake and tsunami crippled the Fukushima facility, Japan relied heavily on nuclear power. Public sentiment against atomic energy has hardened since then, especially as the government and the Tokyo Electric Power Company continue to struggle with stabilizing the damaged reactors.

Most people accept that Japan—which turned off its last active reactor in September—will have to restart its nuclear plants for the time being, but the disaster has definitely turned attention toward safer energy alternatives.

Shimizu actually developed the Luna Ring idea before the Fukushima accident happened, but the ongoing crisis is making people take a fresh look at the plan.

When finished, the belt will wrap 6,800 miles around the equator to guarantee nonstop access to sunlight—with no clouds to block the view—and ensure a steady flow of energy is beamed back to Earth.