Scientists at the University of Southampton found evidence that waves of hot, melted rock are rising up from deep below Africa.

These surges are slowly ripping the continent in two and creating a brand-new ocean.

According to the study in Nature Geoscience, a column of hot mantle sits under Ethiopia’s Afar region and throbs upward like a beating heart.

Africa will (eventually) tear apart

The team found that the tectonic plates—those giant slabs of crust floating on the surface—actually have a big effect on how that hot material flows up from below.

It takes millions of years, but as the plates pull apart in rift zones like Afar, they stretch and get thin—like soft clay—until they eventually break, marking the start of a new ocean.

Dr. Emma Watts, who led the study at the University of Southampton before moving to Swansea, explained that the mantle under Afar isn’t still or consistent; instead, it pulses, and each pulse has a unique chemical makeup. She noted that the separating plates on the surface actually guide these rising waves of semi-melted rock, which really changes how we look at the connection between the Earth’s deep interior and the ground above.

The project brought together researchers from ten different organizations, including the University of Southampton, Swansea, and Lancaster, as well as the Universities of Florence and Pisa, GEOMAR in Germany, the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Addis Ababa University, and the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences.

A peek inside the Earth

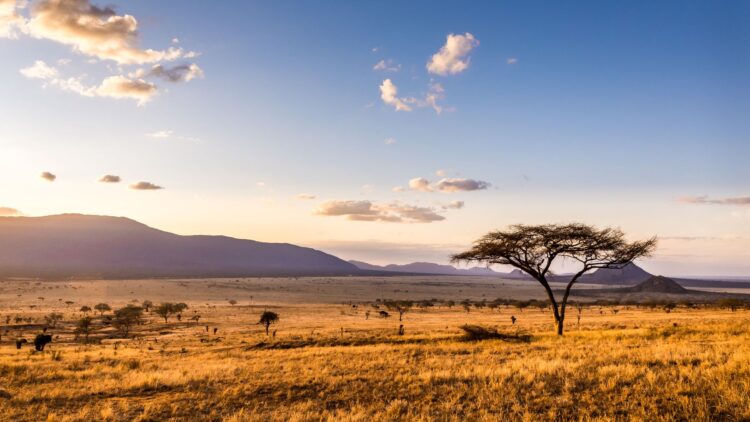

The Afar region is one of the few spots on the planet where three separate tectonic cracks meet: the Main Ethiopian Rift, the Red Sea Rift, and the Gulf of Aden Rift.

For a long time, geologists guessed that a surge of hot mantle—often called a plume—sits under this area, pushing the crust apart and helping to create a future ocean. However, before this, we didn’t know much about the shape of this rising rock or how it acts underneath the separating plates.

The researchers gathered over 130 pieces of volcanic rock from all over the Afar area and the Main Ethiopian Rift.

By combining those samples with previous records and complex computer models, they analyzed the makeup of the crust and mantle, along with the molten rock hidden inside.

The findings reveal a single, uneven column of magma under the Afar area, marked by specific chemical stripes that show up repeatedly across the rift, almost like geological barcodes. The distance between these patterns changes based on what the tectonic plates are doing in each section of the crack.

Tom Gernon, a study co-author and Earth Science professor at the University of Southampton, noted that these chemical stripes indicate the plume is actually throbbing, similar to a heartbeat. He explained that the pulses act differently based on how thick the plate is and the speed at which it’s separating.

In areas where the rift is opening up quickly, like the Red Sea, the surges move more smoothly and consistently, much like blood pumping through a tight artery.

How this affects other things like volcanoes and earthquakes

This fresh research demonstrates that the mantle plume under the Afar area isn’t just sitting there; it’s active and actually reacts to the tectonic plate floating above it.

Dr. Derek Keir, a co-author of the study and Associate Professor of Earth Science at the Universities of Southampton and Florence, stated that they discovered a tight bond between the development of deep mantle surges and the movement of the plates overhead. He pointed out that this really matters for understanding volcanic eruptions on the surface, earthquake patterns, and how continents eventually break into pieces.

Keir explained that the study proves rising mantle material can travel along the bottom of tectonic plates, directing volcanic eruptions to spots where the crust is thinnest. He added that the next steps involve figuring out the speed and mechanics of that flow underneath the plates.

On the other hand, Dr. Watts also noted that collaborating with experts from various fields and schools was crucial for making sense of these underground processes and connecting them to modern volcanic activity. She explained that without using a mix of different methods, you can’t really see the whole picture—it’s like trying to finish a puzzle when you’re missing pieces.