The surface of our world has been in a constant state of flux for millions of years. Continents have wandered, oceans have taken on new shapes, and mountain ranges have soared up and worn away. Yet deep below us, in the unreachable layers of the Earth’s mantle, this activity leaves behind marks that last for ages.

Recently, a team of researchers successfully spotted one of these ancient remnants: a slab of seabed that went under more than 250 million years ago and is still stuck in the mantle transition zone, over 250 miles beneath the Pacific.

Headed by researchers from the University of Maryland and appearing in the journal Science Advances, this discovery carries consequences that could reshape our understanding of the Earth’s interior. By using high-tech seismic imaging—basically a CT scan for the entire planet—the group spotted a surprisingly thick and cold area in the mantle right underneath the East Pacific Rise, which is one of the busiest spots for seafloor spreading on Earth.

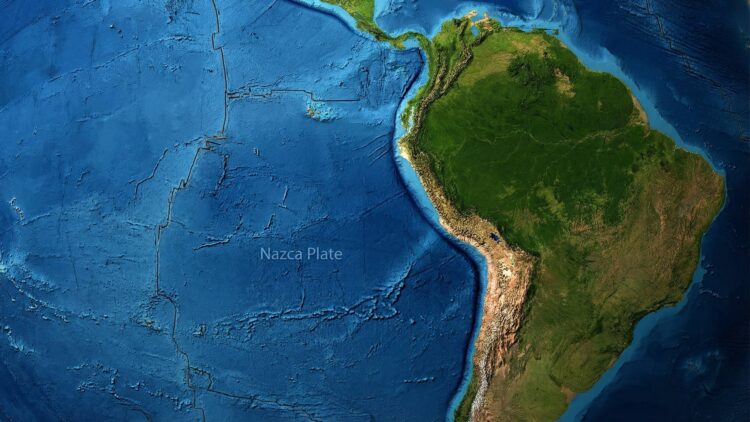

What they uncovered is quite significant: traces of an old subduction zone—the process where one tectonic plate dives under another—that was part of an oceanic plate that vanished hundreds of millions of years ago. Rather than sinking all the way to the Earth’s core as we used to think was standard, this slab got jammed in the transition zone, between 410 and 660 kilometers down. The biggest surprise is that it is still sitting there, acting like a geological time capsule.

Planet Earth is slow af

The study also turned up a surprise: the sinking rock travels slower than current models predict. The team estimates that material moving through the mantle might be up to 50% slower than anticipated, which challenges some basic concepts about the Earth’s internal mechanics. Rather than flowing like a steady stream, the mantle seems to have zones where movement lags or stops altogether.

This sluggishness leads to major consequences. If the mantle blocks certain materials, it could affect processes across the globe, such as volcanic eruptions, the movement of tectonic plates, or even changes in the Earth’s magnetic field. In fact, making sense of these deep interactions is crucial for modeling how planets evolve, not just for Earth, but for other rocky objects in our solar system as well.

How they found the scar kilometers under Earth’s crust

To get this data, the researchers looked at thousands of seismic logs created by waves reflecting off breaks in the mantle. These vibrations, called SS precursors, echo off the boundaries between different layers, giving scientists a way to deduce what the inside of the Earth looks like. By mixing these records with global imaging models and sophisticated statistics, the group managed to build a precise map showing the thickness and features of the mantle transition zone under the Pacific.

Because the quality and amount of data gathered over the last few decades have gotten so much better, scientists have reached a level of clarity they never had before. And the things they have spotted might only be the beginning.

Is this the start of a new kind of deep geology?

This discovery gives us a fresh look at Earth’s remote past, but it also brings up questions that still need answers. How many other fossil structures like this are sitting right beneath us? Could they be influencing geological events on the surface without us even realizing it? And is the Earth’s mantle actually much more complicated than we ever imagined?

The fact is, this finding happens at a perfect time. Geology is currently evolving, driven by new technologies that let us investigate things that used to be invisible. What we are seeing now is a planet that is more active, more intricate, and, most importantly, holds onto its history much longer than we thought.