Using the massive SLS rocket, the Artemis II flight is going to shoot four astronauts inside the Orion capsule on a ten-day trip that swings them just 4,600 miles (7,400 km) past the Moon.

A Crew of Firsts

The team is made up of Commander Reid Wiseman, Pilot Victor Glover, plus mission specialists Christina Koch and Jeremy Hansen from Canada. This flight makes Koch the first woman to go to the Moon, while Hansen becomes the first person from outside the U.S. to make the trip. Together, these four possess a combined 660 days of experience living on the International Space Station and have completed a dozen spacewalks.

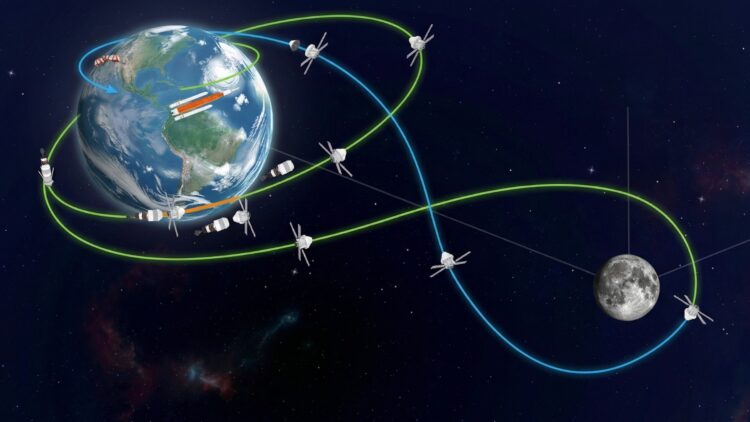

Testing Systems in Earth Orbit

Before they actually head for the Moon, the mission will slip into a really high orbit around Earth for a full day to test Orion’s systems. Once they detach from the top part of the rocket, the astronauts are going to grab the stick to fly manually, spinning Orion around to get close to the spent rocket stage for a practice docking maneuver to see if the ship maneuvers well nearby. Finally, the ship will rotate back and fire up the main engine on the Service Module to start the push toward the Moon.

The Lunar “Slingshot” Maneuver

The Orion capsule holding the four crew members is projected to hit a low point of roughly 4,300 miles (6,900 kilometers) over the lunar surface during its closest flyby, a moment engineers call pericynthion or PC. Using this specific flight path allows the Moon’s gravitational pull to curve the ship’s course around the far side and send it looping back toward our planet.

The Apollo 13 mission took a comparable route to return safely after an onboard explosion, though they skimmed much lower at just 156 miles (251 kilometers) high.

From that much greater height, the Artemis II team will get a view of the full lunar disk during their pass. The wide view in the simulation mimics this perspective, which looks about the same size as a basketball held out at arm’s length.

Depending on exactly how far the Moon is from Earth when they get there, these astronauts might set a new record for the greatest distance humans have ever traveled from Earth, beating the 248,647-mile (400,073-kilometer) mark set by Apollo 13. Regardless, they will certainly be flying nearly 300 times farther out than anyone has ventured since the Apollo era ended over 50 years ago.

Launch Targets and Legacy

Artemis II might take off in just a few days—potentially as soon as February 6—hanging on the results of a critical fueling dry run on the pad at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center. Should everything stick to the schedule, this flight stands to break the all-time record for how far people have traveled into deep space, swinging roughly 4,600 nautical miles past the Moon.

“Since none of us were alive when Apollo happened, we see this as our chance to spark interest in space exploration for a whole new generation of children,” noted Rick Henfling, the mission’s entry flight director. “It’s possible that a child watching what we accomplish with Artemis II grows up to be the very first human to leave footprints on Mars.”

Returning back to Earth

Once the ship swings past the Moon, it starts the trip back to Earth without needing a massive engine blast. Instead, Orion counts on the gravitational pull from both the Earth and Moon to steer it home on a route that saves fuel.

The team will keep running system checks, fitting in more practice with manual controls and testing out the radiation shelters. Tiny engine firings will tweak their course to line up the reentry. As Orion gets close to Earth, the service module will detach and disintegrate in the sky, uncovering the crew capsule’s heat shield. The pod is going to slam into the atmosphere at high velocity, reaching temperatures around 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit while hot plasma cuts off their radio signal for a short time.

Once the descent slows, Orion will pop its parachutes to brake for a splashdown in the Pacific waters near San Diego. If the capsule ends up floating upside down or sideways, inflatable bags will flip it upright. Recovery teams from the U.S. Navy will be there to retrieve both the ship and the astronauts, usually finishing the job in under two hours.