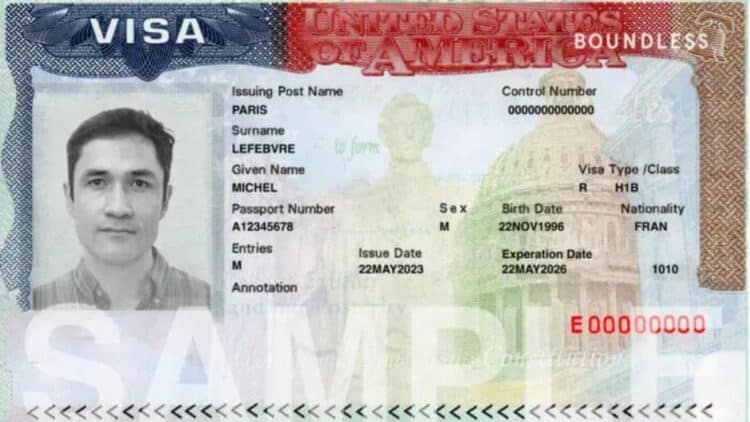

A few days ago, an immigration regulatory measure came into effect that has the wolves of Wall Street breathing fire. On September 21, 2025, a single fee of no less than $100,000 came into effect for new H/1B applications. This will last for 12 months and applies to all applicants outside the United States. However, it excludes renewals and allows extensions for “national interest,” quote unquote.

The annual quota for new H/1B visas remains at 80,000 for the coming fiscal year, 2026, and the quota has already been completely filled.

This situation does not sit well with Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan, who says there will be “pushback.” This is not surprising, given that his company is one of the largest applicants for H-1B visas. Meanwhile, the White House insists that this measure is simply protecting American workers.

How many people arrive on H-1B visas?

The labor market is already quite saturated, and mass immigration, however skilled, only makes native workers more vulnerable. In 2023 alone, no fewer than 265,777 H-B1 visas were approved at embassies and consulates. The following year, in 2024, 219,659 visas were issued. In just two years, nearly 1 million skilled workers were admitted, which obviously drives down wages in the U.S. labor market.

Demographically, it is clear where the vast majority of H-B1 visa workers come from. Seventy-one percent of the beneficiaries of this type of visa come from India; 11.7% come from China, and the rest come only from the Philippines, Canada, South Korea, Mexico, Taiwan, Pakistan, Brazil, and Nigeria. These last 10 countries account for 7% of the visas.

James Dimon vs. White House

James Dimon believes that these types of visas allow experts to move around the globe, ensuring that the United States remains an attractive country that draws in the most active workers who can create wealth. JPMorgan will be the largest sponsor in 2024.

Other CEOs do not share exactly the same view: Jensen Huang (Nvidia) considers the figure of $100,000 too high. Sam Altman (OpenAI) is more in favor of “raising the bar” and aligning incentives.

J.P. Morgan economists estimate that 5,500 fewer work permits per month will result in a new cost (i.e., they will have to pay a more competitive salary to workers already in the country instead of bringing in cheaper labor from abroad). They lament the high cost of consular processing.

The government is not messing around: they argue that the H-1B visa is being abused to replace workers and drive down wages. By setting a bond of $100,000 for each visa, they discourage this use and prioritize the highest-paid talent. This type of visa has been used to pay lower average wages and thus obtain greater profits for the company. In sectors where there are a large number of H-1B visas (such as technology), this is associated with salaries between 2.6% and 1.01% lower for native computer scientists.

Possible backfire of the tariff

However, it’s not all roses: by restricting this type of visa, multinationals can also increase employment in overseas subsidiaries (offshoring, as it is commonly known). This additional hiring would be shifted to Canada, India, and China. For each visa refusal, they can hire between 0.4 and 0.9 workers abroad.

For now, this new $100,000 tariff is uncomfortable but easily manageable for large companies such as Bi-Tek, which can absorb the cost and attract more talent if there is less competition.

The losers could be start-ups, rural hospitals, and sectors with narrower margins. The quota for 2026 is already closed, so the impact will not be seen until 2027. What we know for certain that it will take at least a couple of years to see how the job market is affected by this measure. Only time will tell.