More than 500 years ago, while a medieval scribe was carefully copying a religious manuscript by hand, a cat walked across the pages while the ink was still wet leaving marks of its paws. Although this might seem just a curious anecdote, this finding allows us to better know how people who copied books in the Middle Ages worked, how they lived with animals, and what role cats had in places where producing texts was important. So, let’s learn more about this animal!

A cat leaving its paw marks

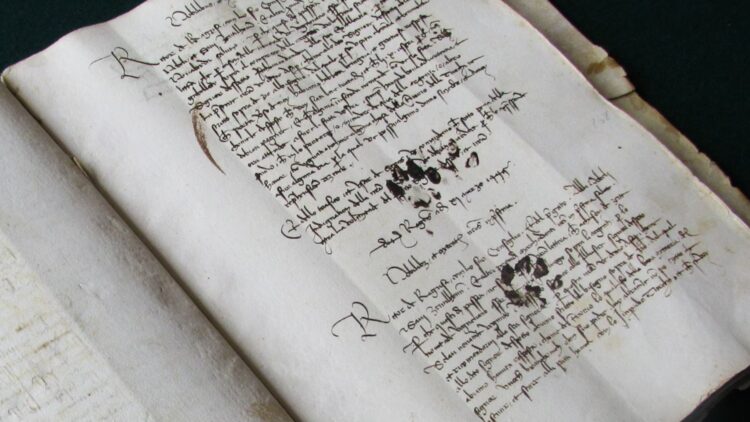

We have to thank this discovery to with a doctoral student named Emir O. Filipović who was examining medieval docuemnts at the historical archive of Dubrovnik, Croatia. There, he found very special marks on the manuscript: paw prints left by a cat.

The thing is that the cat was walking on the pages while the ink was still fresh and left a sequence of dark mars that can be seen even today! And this happened about in the decade of 1470…

Filipović took a picture of the marks and shared it with other researchers. What started as a casual examination became a very interesting example to explore the material reality and daily life of the medieval world.

How medieval manuscripts were made

The manuscript with the marks is a religious work copied in the north of Europe during the 15th century. At that time, books were handwritten using plant-based inks on the parchment, which was made from animal skin.

After writing, the manuscript had to remain open so that the pages could properly dry. It’s probable that the scribe had left for a few minutes and, while the ink was still fresh, the cat walked on the open manuscript.

Today, this example is considered one of the oldest known cases of direct interaction between a domestic animal and a manuscript in the process of being produced. It shows how easily everyday events could become part of history.

Cats in medieval workshops, monasteries, and libraries

Even though this might seem rare, it was very common to see cats in places where books were written in the Medieval Ages.Why?Because manuscripts were vulnerable to mice and other rodents that could damage parchment and destroy valuable texts, so these animals played a practical and essential role because they helped control pests and protect manuscripts from harm.

Basically, they lived and worked alongside scribes: they slept near desks, walked along shelves, and moved freely through libraries and monasteries. The cat’s footprints simply reflect the normal environment in which medieval books were created.

Medieval cats and manuscripts

The manuscript from Dubrovnik later inspired an exhibition called “Paws on Parchment,” organized at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. The exhibition explored the presence of these animals in medieval manuscripts from different perspectives: cats as illustrated figures in book decorations, as symbolic animals in medieval culture, and as real creatures that left physical marks on historical documents.

Among the objects displayed was the very codex containing the cat’s footprints. The exhibition also included manuscripts from different regions of Europe and the Islamic world, showing how cats appeared across many cultural contexts.

Apart from real footprints, medieval manuscripts often contained drawings and miniature illustrations of cats in the margins chasing mice, participating in everyday scenes, or interacting with humans. These images reveal how familiar people were with cats and how they saw them as both helpful protectors and mysterious animals.

To sum up

The story reminds us that history is not only made of major events and famous figures. Sometimes, ordinary moments and unexpected accidents become a lasting record.