We reside in the cosmos as Sagan saw it—incredibly huge and truly grounding. It is a reality that, as he frequently pointed out, does not revolve around humanity. We represent just a tiny particle. Our time here might be short-lived—a quick spark of light in a massive, dark sea. On the other hand, we might stick around, figuring out how to rise above our darker impulses and old grudges to eventually spread across the stars. We might even discover neighbors out there living in far-off, super-advanced societies—what Sagan might call the ancient ones.

Nobody has ever described the cosmos, with all its confusing magnificence, quite like Sagan. Although he passed away thirty years ago, those old enough to recall him can easily imagine his voice, his love for saying “billions,” and his childlike excitement for figuring out this universe we are fortunate to call home.

Rising to the Stardom (badumtss) in the scientific community

He lived a frantic life, juggling several careers at once, almost as if he sensed his time was short. His resume included teaching astronomy at Cornell, penning over twelve books, contributing to NASA’s robot missions, and editing the journal Icarus, yet he still managed to constantly, perhaps obsessively, get himself on television. He essentially became the resident space expert for Johnny Carson’s “Tonight Show.”

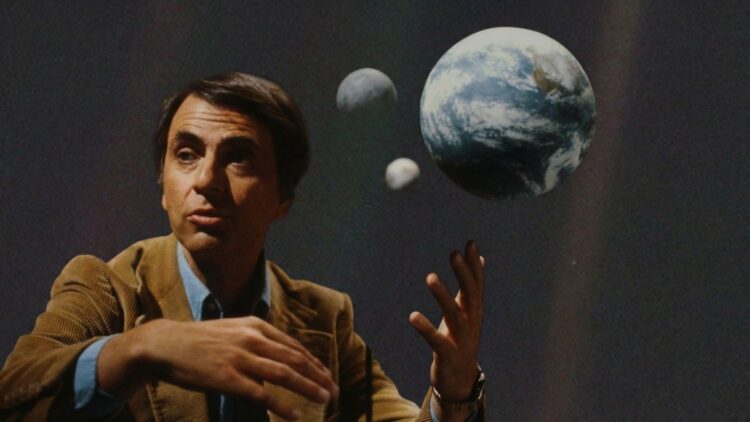

Later, finding an incredible second wind in his mid-forties, he developed and presented the thirteen-episode PBS show, “Cosmos.” The series premiered in the autumn of 1980 and eventually found an audience of hundreds of millions around the globe. Sagan became the most well-known researcher in the US—the very personification of science.

Sagan: A career well preserved for posterity

Luckily, his professional journey is thoroughly recorded, and those materials are now housed at the Library of Congress, which acquired them from Druyan using funds contributed by MacFarlane. (Technically, it is known as the Seth MacFarlane Collection of the Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive.) The records landed on the library’s loading platform in 798 cartons—apparently, Sagan was a bit of a hoarder—and following seventeen months of organization, the files became accessible to investigators last November.

This collection offers an intimate look at the star scientist’s hectic life and, of greater significance, provides a historical account of how the American public viewed science during the latter part of the twentieth century. Through the relentless tide of letters arriving at his Cornell office, the voices of average citizens come through clearly.

These correspondents considered Sagan the guardian of scientific legitimacy. They confided their grand schemes and edge theories to him. They described their personal dreams. They pleaded for an audience. They sought the truth, and he was their guide.

The Age of Wonder and Optimism

The Sagan papers bring back the adventurous spirit of the 1960s and 70s, showing a time that resisted conventional wisdom and authority, with Sagan situated right in the heart of that intellectual stir. He served as a balanced mediator. For instance, he realized UFOs were not actually alien vessels, yet he had no desire to quiet the believers, so he assisted in arranging a large debate on the subject in 1969 to let every perspective be heard.

The cosmos itself felt distinct in those days. At the time Sagan was growing up, space exploration had serious momentum: there were no limits to our extraterrestrial ambitions. By way of telescopes, automated sensors, and the Apollo moonwalkers, the universe was exposing its secrets at a breakneck, dazzling speed.

The famous “Pale Blue Dot”

Think back to the early 1990s, when Voyager 1 was making its way to the edge of the solar system; Sagan was one of the people who convinced NASA to turn the probe’s camera around to face Earth, which was billions of miles distant by that point. In the resulting photo, the world appears as nothing more than a blurry speck caught in a beam of light. What a strike to humankind’s ego: the ultimate proof that we are nothing but a speck of dust in the universe.