You may not have noticed—how could you?—but Earth recently went through a rare S4 solar radiation storm, the strongest one we have seen since 2003—it is a big deal for satellites and astronauts, but poses no danger to us on the ground. Even though a strong G4 geomagnetic storm grabbed all the attention with amazing light shows around the globe this week, a much quieter but historically huge space weather event was taking place right alongside it.

NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center confirmed that on Monday, January 19, Earth was hit by the biggest solar radiation storm since October 2003, eclipsing even the famous storms that happened around Halloween that year.

How can a star like our Sun have storms?

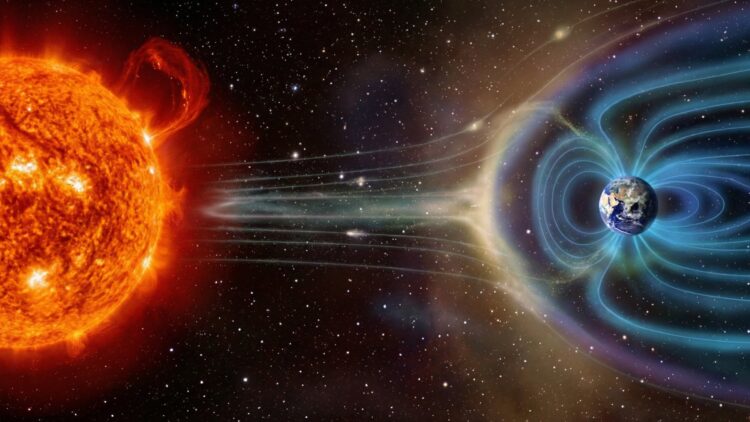

These events happen when a huge magnetic blast on the sun, usually involving a cloud of plasma called a coronal mass ejection, sends charged particles—mostly protons—flying at insane speeds.

According to NOAA, those particles can move at a significant percentage of the speed of light, closing the 93-million-mile gap between the sun and us in just ten minutes or so.

When they get here, the strongest protons punch through our planet’s magnetic shield and follow the field lines down to the poles, where they crash into the upper atmosphere.

Despite what it might sound like, we are safe down here…

NOAA ranks solar radiation storms from S1 to S5—minor to extreme—using data on high-energy protons collected by their GOES satellites. The storm on January 19 climbed all the way to S4, meaning it was severe.

Even though that sounds scary, storms like this aren’t dangerous to us down here because Earth’s heavy atmosphere and magnetic shield block the radiation well before it gets to the surface.

It is important to note that the radiation didn’t actually hit the ground this time. Space weather physicist Tamitha Skov pointed out that the particles were somewhat soft; even though the total amount of radiation was historically high, the individual particles didn’t have enough energy to punch through to where we live.

…Satellites and airplanes, not so much.

Things look a bit different once you get high above the surface.

Severe storms ramp up radiation risks for astronauts as well as flight crews and passengers on polar routes, since Earth’s magnetic shield is weaker in those areas.

Satellites are also in the line of fire, as energetic particles can mess with their electronics, confuse sensors, and overload their instruments.

During this event, some forecasters noticed temporary gaps in their data, likely because the flood of protons made it hard for spacecraft to get clear readings.

Are solar radiation storms and geomagnetic storms the same thing?

No, they are actually separate events with different impacts.

Radiation storms happen when the sun shoots out fast particles, whereas geomagnetic storms kick off when choppy solar wind clashes with our planet’s magnetic field.

You usually get a geomagnetic storm when the magnetic field from a CME crashes into Earth’s own field, though fast streams of wind pouring out of solar coronal holes can cause them too.

These clashes can spark auroras and mess with navigation tools, radio signals, and power grids.

What does this mean for normal, everyday life on Earth?

Big solar storms can push unwanted electrical currents through the long power lines that Transpower manages. If those currents hit transformers at substations or big hydro dams, they could cause serious damage.

“We have been watching this solar storm closely ever since that blast of plasma left the sun on Sunday,” the spokesperson noted. “It hit at 8:40 am today, creating some magnetic currents in our power grid, but the levels are low enough that we don’t need to take any special action.”

They had a backup plan ready to switch off certain circuits to handle the effects, but even if they had to do that, it wouldn’t have cut power to homes or businesses. Local agencies are understanding the risk of solar storm disruptions better these days, and many of them have response plans ready to go.In fact, Nema ran a simulation of a massive G5 event in the Beehive bunker back in November.