A team from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan has built the tiniest programmable, self-driving robots ever made—microscopic swimmers that can react to the world around them on their own, keep running for months, and only cost a cent apiece.

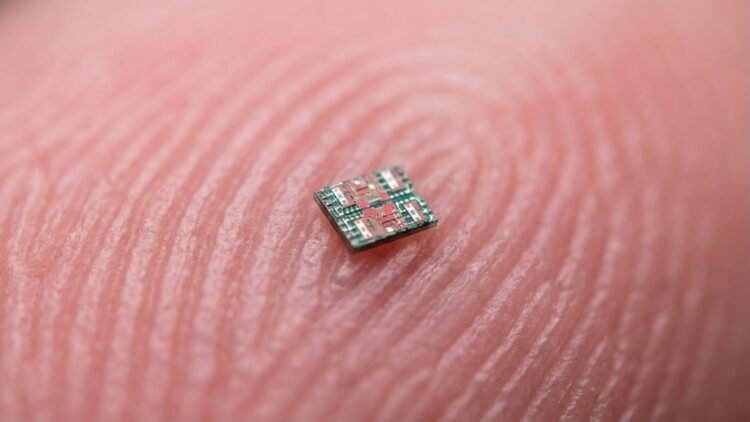

This miniature robot packs both a computer and sensors, yet it’s small enough to perch right on the swirl of a fingerprint. You can hardly see these things without a microscope since each one is tinier than a grain of salt, measuring roughly 200 by 300 by 50 micrometers. Since they function at the same size as many germs, these bots could be a game-changer for medicine by checking up on single cells, or for industry by building microscopic gadgets.

These light-powered bots come equipped with tiny onboard computers, allowing them to follow complicated routes, detect heat nearby, and steer themselves in response.

As detailed in Science Robotics and PNAS, these machines don’t need wires, magnets, or external remote controls to work, which makes them the first programmable robots of this size to be genuinely self-reliant.

Marc Miskin, the lead author and a professor at Penn Engineering, points out that they have successfully shrunk self-driving robots by a factor of 10,000.

He adds that this achievement unlocks a completely different playing field for programmable machinery.

World Record: finally, a nanobot smaller than a millimeter

Electronics have been shrinking for ages, but robotics hasn’t been able to keep up. Miskin notes that creating independent robots smaller than a millimeter is extremely tough. Researchers have basically been trapped by this obstacle for four decades. In our everyday world, forces like gravity and inertia rule the day because they depend on volume.

However, once you shrink down to cell size, surface-related forces like drag and stickiness take control. Miskin explains that at that scale, trying to swim through water feels like pushing through tar. Basically, the movement methods used for big robots, like legs and arms, usually fail when things get that small.

Miskin points out that microscopic limbs snap easily.He also mentions that they are incredibly difficult to manufacture. That meant the team had to invent a completely fresh way to move, one that works with the weird physics of the microscopic world instead of fighting it.

How can something so teeny tiny be autonomous?

For a robot to be genuinely independent, it requires a computer to think, electronics to feel and steer, and miniature solar panels to run it all—and everything has to fit on a sliver of a chip less than a millimeter wide.

That is exactly where David Blaauw’s group from the University of Michigan stepped in. Because it carries a full computer onboard, the robot can accept commands and execute them on its own.

Blaauw’s lab currently holds the title for building the smallest computer in existence. When Miskin and Blaauw ran into each other at a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) talk five years back, they instantly saw that their technologies would work perfectly together.

Blaauw notes that they recognized the propulsion system from Penn Engineering and their own microscopic computers were practically made for one another. Even so, both teams had to put in five years of serious effort to finally produce a functioning robot.

What this entails for the next generation of microscopic robots

Later iterations of these robots could handle tougher code, move quicker, include fresh sensors, or function in rougher spots. Basically, the current model acts as a flexible foundation: the propulsion system pairs perfectly with the electronics, the chips are cheap to mass-produce, and the layout makes it easy to add new abilities.

Miskin explains that this is really only the beginning. He notes that they have proven you can pack a brain, a sensor, and a motor into a speck that is barely visible, yet still have it last and run for months.

With that groundwork established, you can start stacking on all sorts of intelligence and features. He adds that this paves the way for a completely new era of microscopic robotics.