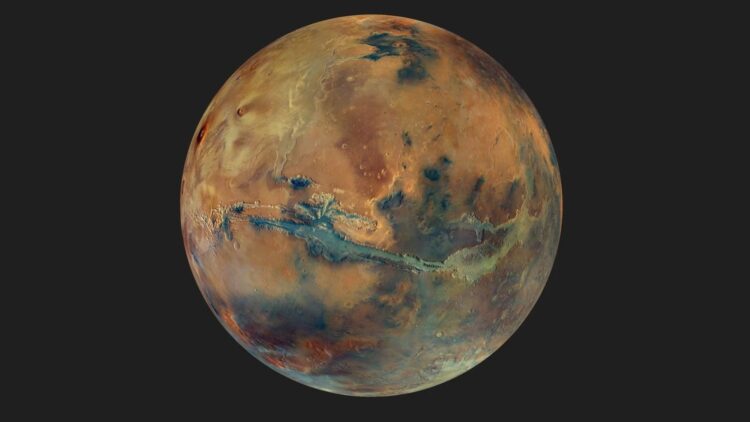

ESA’s first mission to another world, the Mars Express orbiter, began circling the Red Planet on June 2, 2003. Ever since, the spacecraft has been mapping the terrain using the High-Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC), a device created by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) and its business partners. To celebrate the mission’s 20th birthday, the team gathered last Friday, June 2, at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany.

During the event, the orbiter livestreamed a collection of global color mosaics back to Earth. Creating this image required a special high-altitude project by the science team and some cutting-edge processing techniques.

The outcome is an incredibly detailed and colorful view that gives us a fresh look at the Martian environment. It shows us exactly what the ground is made of, points out where water used to run, and tracks weather happening right now.

A mission to map planet Mars

For nearly two decades, the camera has charted almost the entire Martian landscape in 3D and color, capturing details sharper than anything we’ve seen before. It manages this using four specific color filters—red, green, blue, and infrared—along with five other specialized sensors for angles and brightness. Run by the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, the instrument was initially supposed to survive for just one Martian year, or roughly 687 Earth days.

However, it performed so well that ESA has kept extending the project, most recently pushing the end date to late 2026. The team at the German Aerospace Center in Berlin was responsible for scheduling and taking those high-altitude shots. Dr. Greg Michael, an astrophysicist at the Free University of Berlin who helps lead the camera team, handled the image processing and built the color model.

The group plans to release a formal paper soon, and they will also upload the map data to ESA’s public archives for anyone to access.

Putting together an accurate photograph

The camera went online in January 2004 and has since photographed nearly the whole planet, with details ranging from 20 to 50 meters in size. Typically, the probe snaps pictures from about 300 km up, right when its orbit swings closest to the surface.

However, for this composite view, they used 90 separate shots taken from much higher altitudes—between 4,000 and 10,000 km—which captured massive areas roughly 2,500 km across at a lower resolution of 2 km per pixel. Despite that, many parts of the map still show off the gear’s maximum sharpness of 12.5 meters per pixel.

The range of colors they managed to capture is also pretty impressive. It is usually tough to get photos that show the ground’s true colors because the Martian atmosphere is constantly changing in clarity.

Differing amounts of floating dust scatter and reflect the light, which makes the colors look inconsistent between different shots. To handle this, space agencies usually rely on image processing to mute those color shifts over large distances.

Mars reveals its true colors

For this project, they ran a new high-altitude survey to build a global color model, which the team then used to calibrate every single photo in the composite. This approach preserved color differences across vast distances, producing a view of Mars with more variety in its hues than we have ever seen.

Those shifting tones also give us clues about what the ground is made of, confirming the massive amount of oxidized iron in the surface soil. That rust is exactly why we call it the “Red Planet,” but looking closer reveals dark patches that show up as blue, grey, and black.

These dark zones are actually layers of volcanic sand that astronomers have been spotting through telescopes for centuries. The wind has piled most of this grit into large dune fields made of fresh basaltic minerals, much like the volcanic sands and dunes we find here on Earth.

You can also see patches of lighter volcanic sand that were worn down over time by water that flowed across the surface roughly two to three billion years ago. The Curiosity and Perseverance rovers have actually studied this material up close, finding clay deposits in the Gale and Jezero craters.