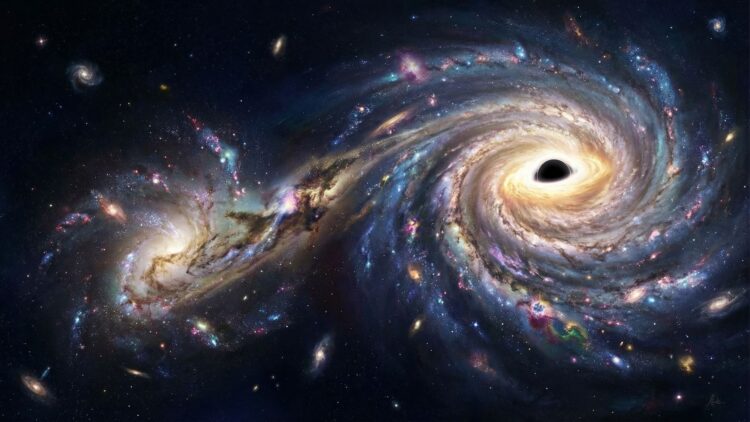

We might be on track to hit a supermassive black hole a lot sooner than anyone expected. Tucked away inside the Large Magellanic Cloud—that dwarf galaxy spiraling tighter and tighter around us—astronomers have spotted clues of a huge, unseen object about 600,000 times heavier than our Sun. Since that galaxy is bound to crash into ours eventually, this black hole is essentially hitching a ride straight toward us.

Even more fascinating is the fact that this black hole sits in a rare weight class, coming in at under a million solar masses. Verifying that it’s real would provide a crucial piece of the puzzle in figuring out how these dark giants evolve from stellar remnants into the true monsters that hold billions of Suns’ worth of mass.

Astrophysicist Jiwon Jesse Han from the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) spearheaded these findings, which are now up on the arXiv preprint server and under review by The Astrophysical Journal.

Trying to catch an invisible giant

Finding black holes is often a real challenge. Unless they happen to be feeding—heating up material until it glows brightly—they don’t give off any radiation we can pick up. This forces researchers to use clever workarounds, like hunting for stars with strange orbits that only make sense if something invisible is pulling on them.

The main way they handle this is by measuring weird orbital paths. For instance, tracking orbits in the heart of the Milky Way is exactly how astronomers confirmed that Sagittarius A* is real and determined it weighs as much as 4.3 million Suns.

Han and his team didn’t rely on orbital patterns, though. Instead, they focused on a different kind of movement involving hypervelocity stars—rare objects zipping around much faster than typical stars, with enough speed to potentially escape into deep space.

Plenty of these speed demons are racing through the galaxy’s outer halo with no clear destination. The method behind their acceleration gave researchers a hunch that these stars could act as guides to invisible black holes. This speed boost comes from something called the Hills mechanism, a three-way interaction involving a black hole and two stars. Sooner or later, that gravitational struggle ends with one member of the trio getting kicked out across space at incredibly high speeds.

Following the breadcrumb star trail

The now-retired Gaia space telescope spent years charting everything in the Milky Way, tracking not just the speed and direction of objects, but also their exact 3D locations—a job that is surprisingly difficult.

With that data in hand, the team took a fresh look at 21 hypervelocity stars in the galaxy’s outer edges that fit the pattern of the Hills mechanism. These are all Type B stars—massive, scorching hot, and destined to die young—which implies their rapid journeys through space haven’t been going on for very long.

The study involved backtracking the speed and direction of these stars to find their starting point, while carefully eliminating other potential causes for their acceleration. They managed to successfully pinpoint the origins of 16 stars. Seven of them started out near Sagittarius A*, right in the heart of the Milky Way.

The other nine, though, look like they originated in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Taken together, they point to being ejected via the Hills Mechanism by an object weighing roughly 600,000 solar masses—a black hole hiding somewhere inside.

Future massive black hole (collision)

Right now, the Large Magellanic Cloud is orbiting the Milky Way from a distance of about 160,000 light-years. Its long, slow fall toward us isn’t simple; it’s an ongoing cosmic dance that recent estimates suggest won’t end in a collision for another 2 billion years. Once the galaxies finally merge, the black hole inside the Large Magellanic Cloud—if it exists—will drift to the center and, after countless eons, fuse with Sagittarius A* to create an even larger black hole.