Researchers working on the Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project think they might have actually found a sample of DNA from the famous artist and inventor himself.

The results are in a preliminary report, and they need to run more tests to confirm if this really is da Vinci’s genetic material from over 500 years ago. The team says the study offers hints rather than solid proof, but it does prove that extracting useful biological details from fragile, expensive historical pieces can be done.

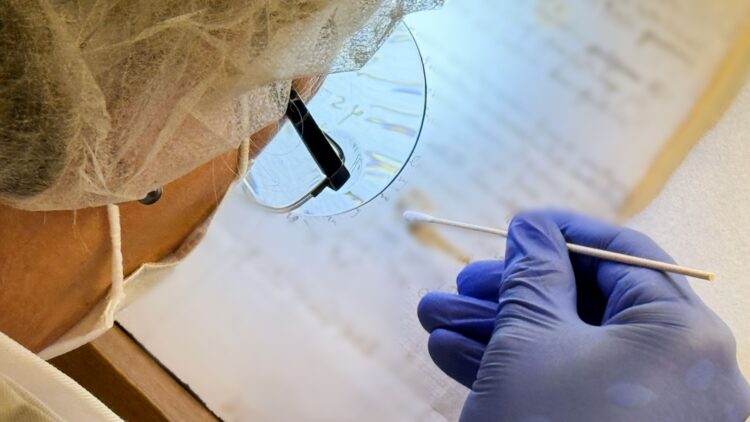

The scientists came up with a clever way to pull DNA from humans, plants, animals, and even germs out of old wax letter seals and the paper itself.

A (genetical) fingerprint hidden in the Holy Child

A statement from the project says that objects people thought were biologically empty actually act like living records of their surroundings. In their early version of the paper, the team describes how they carefully took samples from the Holy Child, a chalk sketch that might be by da Vinci.

Using modern sequencing tools, they successfully pulled out biological data, which included traces of orange trees grown in the Tuscan Medici gardens and some degraded human DNA.

Nobody knows exactly who left this DNA behind. It might belong to the artist himself, or maybe just people who touched the drawing later on. One thing is certain: some of the DNA had Y-chromosome markers, meaning it definitely came from a man. This person appears to belong to a genetic group that’s typical in the Mediterranean, particularly in central and southern Italy (where the painting stayed for centuries, duh).

That area covers Tuscany, which is Leonardo’s home region. When the team swabbed other items linked to da Vinci, such as a 500-year-old letter written by a relative, they picked up on a matching Y-chromosome signal. Interestingly, this specific signal didn’t show up in paintings by other famous European masters from that era.

Tracing Da Vinci’s DNA back to his tomb

The results suggest a common family connection between the da Vinci items, which definitely merits more study. The team now wants to swab other artworks and objects that definitely belonged to da Vinci to see how they compare.

Then, they’ll have to match those findings against confirmed living descendants of the artist. The main goal is to prove where da Vinci is actually buried and to rebuild his genetic code from all those years ago.

Jesse Ausubel, the project chair from The Rockefeller University, says that even if a confirmed DNA match is still down the road, success is basically inevitable now that they’ve broken this new ground. For nearly ten years, researchers have been working to trace da Vinci’s bloodline back in time and forward to more recent generations.

They recently identified a few living descendants and a family history that goes all the way back to 1331. People say da Vinci is buried in a little chapel in France’s Loire Valley, but some historians aren’t sold on the idea that he’s actually there. Right now, researchers are digging up a da Vinci family tomb in Italy to get genetic data from his relatives.

A potentially bulletproof method to discern original masterpiece from forgery

Evolutionary biologist S. Blair Hedges, who wasn’t part of the study, told a reporter that this project is aiming for one of the toughest goals in ancient DNA research, but he thinks their methods are impressive.

Ausubel says the project has built a strong foundation, creating a way to spot biological signs on old art or documents using DNA and microbes. The new skills and groundbreaking techniques developed here can, and definitely will, be used to learn more about other important figures from history.