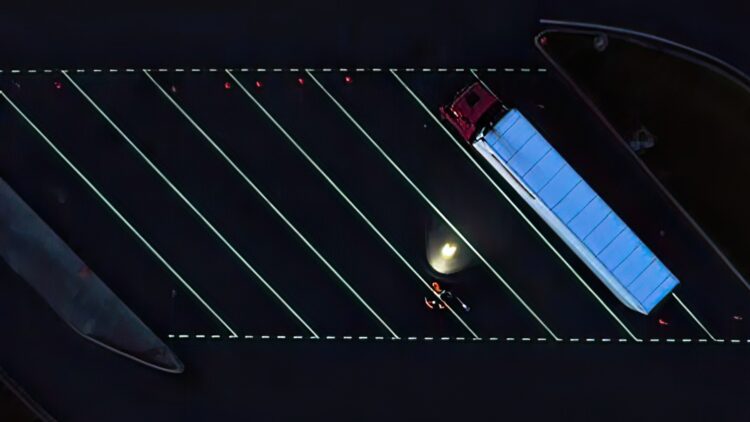

Imagine being able to drive along a road at night without the light pollution from streetlights. However, the light emitted by your car’s headlights is sufficient to see perfectly. The paint on the road gives off a soft, futuristic glow. We are not talking about a fictional film, but a reality of traffic in the Netherlands. In April 2014, the first section known as the ‘photoluminescent road’ was inaugurated.

The goal was to kill two birds with one stone: effectively increase road safety while saving large amounts of electricity.

Photoluminescent roads

It all came about thanks to Daan Roosegaarde and his Studio Roosegaarde, known for its works of ‘techno-poetry’. Roosegaarde—who is more of an artist than a designer, in the best sense of the word—sought to create a network of traffic routes that was more interactive and sustainable. The project required a great deal of engineering and development work, so they partnered with Heijmans Infrastructure, a specialised Dutch company.

Pilot prototypes were carried out on a small 500-metre stretch of the N329 road. It was located near the town of Oz, in the province of North Brabant. The test was a success, as it replaced costly (and polluting) street lighting with an energy-neutral solution on the less travelled sections of the road network.

How does this photoluminescent road technology even work?

The mechanism that makes this night-time glow possible is known as phosphorescence. The road acts as a continuous passive solar collector, unlike retro-reflective road markings, which only reflect the light that hits them. To make it glow at night, the active ingredient in the paint is a strontium aluminate-based pigment. This material is capable of being 10 times brighter than older phosphorescent pigments, so it stores much more light and is able to emit it for a longer period of time.

This pigment absorbs energy from sunlight–especially ultraviolet (UV) light. This charging process does not require any external electrical connection, only sunlight. Once night falls, the material slowly begins to release the stored energy, hence its photoluminescent quality. This gradual release of energy is visible as a yellowish-green glow, ideal for human vision in the dark. The system was designed to maintain constant visibility for up to eight hours after sunset.

Aesthetic success and its Achilles heel

The bright lines project enjoyed undeniable initial success and recognition. Driving along this road felt like a fairytale experience and demonstrated the potential for innovation in traffic management. However, the pilot test on the N329 road quickly revealed flaws in the technology.

The luminescence became inconsistent, depending on whether the sun would shine brightly throughout the day. On cloudy days or in adverse weather conditions – such as heavy rain or humidity – the rain did not charge sufficiently. This was a serious mistake in a country like the Netherlands, which is not particularly known for having a large number of sunny days and clouds throughout the year.

Another primitive aspect was the price of the photoluminescent paint. Subsequent tests in countries such as Malaysia revealed that the material is up to 20 times more expensive than standard thermoplastic paint. In addition, it requires application every 12 to 18 months, which negates any potential long-term energy savings, at least in less developed countries with smaller budgets for this type of infrastructure.

Apart from this, the brightness degraded too quickly at night, compromising road safety and reliable lighting. While it could provide many hours of lighting in summer, the long winter nights left the road completely dark in the middle of the night. Due to these visibility challenges in wet and dark conditions, the project expansion was put on hold.

For now, this technology has been put to alternative uses in low-risk environments. It has been added to the Bango cycle path, a bicycle lane in Nuenen, where visibility is less critical than on a highway… and where aesthetic value is the main objective.